Microbiome - Introduction

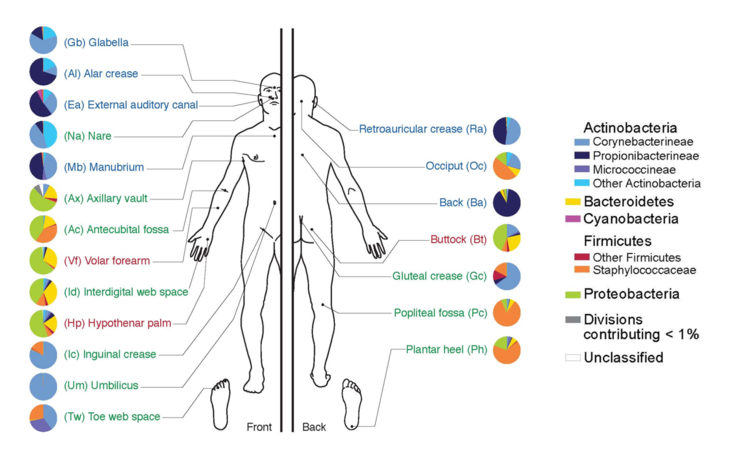

The term "microbiome" in its broadest sense is used to describe all microorganisms colonizing a host organism, i.e. bacteria, archaea, viruses and eukaryotic microbes. The number of these microbial cells in comparison to the number of human body cells in adults has an estimated ratio of about 10:1. Such microbial biofilms mainly colonize the gastrointestinal tract, but also other body cavities, mucous membranes and the human body in general, and in that way significantly affect the functions of the human organism.

In its narrower sense the microbiome encompasses all the genetic information of microorganisms in a host organism and is attributed to Joshua Lederberg. After completion of the Human Genome Project, he postulated that molecular genetic data alone cannot be meaningful, as microbiota profoundly influence the health status of humans, especially as part of the human metabolic system.

The Human Microbiome

The colonization of the human body with microorganisms occurs predominantly in a symbiotically or commensal relation, i.e. human host and its microflora either develop a mutually beneficial relationship, or is considered neutral, i.e. without an apparent advantage for both sides. Symbiotic relationships developed throughout the evolution of the human metabolism, and are shaped by the environment and cultural settings of people, and as such have a strong epigenetic component.

Research

In the last 10 years, the number of publications related to microbiome research has increased exponentially. Despite intensive research, the microbiome still is not well understood. After the National Institute of Health (NIH) launched the US Human Microbiome Project for sequencing the genomes of all microorganisms that colonize humans in 2007, numerous other projects and initiatives followed (for a selection see here). All these studies focused largely on the digestive and urogenital tract, but also on the nasopharyngeal passages, and the skin. A free database has been set up to facilitate cooperation between interested groups.

Over time, and increasingly, other regulatory aspects of the microbiome came into focus.

Functions of the microbiome in the healthy organism

A diverse, balanced microbial system, covering the digestive tract of its host as a biofilm, supports the complex metabolic system of humans, and vertebrates in general. The microbiome also is involved in the development of the body's defense system suppressing pathogens and protecting our body against diseases.

If there is an imbalance or a disturbed communication between the body's own cells and its microbial inhabitants, the microbiome may contribute to the development of disease or even cause such, e.g. by release of toxins, change of the gene expression patterns, or triggering inflammation.

Source: Facharztwissen

Several factors can cause disturbances in the microbiome homeostasis, e.g. stress, changed eating habits, medications, environmental factors as well as genetic predispositions the latter manifesting themselves in the course of individual development.

A well described example are genetic alterations in the NOD2 gene that predispose for Crohn's disease, a chronic inflammatory bowel disease. The NOD2 gene normally regulates the composition of intestinal microbiome by the generation of so-called defensins, which are small 33-47 aa long peptides that fight microbial pathogens, but also defend against pathogenic fungi and toxins. This defense mechanism is subject to a regulative feedback loop by bacteria, thus the microbiome and Nod2 gene activity are controlled mutually.

The lining of the intestine (mucosal barrier) seems to play an important role in maintaining a healthy intestinal environment. Lesions in this barrier resulting in the penetration of pathogens and subsequently, lead to an overreaction of the immune system, i.e. to inflammatory responses and often corresponding disease phenotypes.

To date, a variety of diseases have been described to be microbiome-induced or influenced:

| Disease Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|

| Adipositas / Obesity | REVIEW: Postgrad Med J. 2016 May and references therein; 92(1087):286-300 |

| Atopy / Allergy / Asthma | Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Aug; 16(4):390-5 and References therein |

| Anxiety | Biol Psychiatry 2009;65:263–7. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011;23:255–64 |

| Autism | Cell 2013;155:1451–63. J Pharmacol 2011;668(Suppl 1):S70–80. Anaerobe 2010;16:444–53. J Psychiatr Res 2015;63:1–9. |

| Autoimmune Disorders | DNA Cell Biol. 2016 Jul 27. [Epub ahead of print] J Clin Invest. 2011 Mar 1;121(3):966-75 |

| Colitis ulcerosa | Mucosal Immunol. 2013 Jul 31. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.55 |

| Diabetes Type I | BMC Med 2013;11:46. Diabetes 2013;62:1238–44. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e71108 Nature 2012;490:55–60 ISME J. 2011 Jan;5(1):82-91 PLoS ONE 2011;6:e25792. |

| Cancer | Nat Rev Cancer 2013;13:759–71. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:9862–7. Cell Mol Immunol. 2011 Mar;8(2):110-20; Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;70:183–194 Mutat Res. 2007 Sep 1;622(1-2):58-69 |

| Depression | Biol Psychiatry 2013;74:720–6 Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26:1155–62. |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) | Cell Host Microbe (2014) 15:382–92 PLoS ONE 2013;8 PLoS One (2012) 7:e39242 Am J Gastroenterol (2012) 107:1913–22 |

| Morbus Crown | J Crohns Colitis. 2013 Dec 1;7(11):e558-68 PLoS One. 2013 Oct 2;8(10):e76962 Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105:16731–16736 Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Dec 13;102(50):18129-34; |

| Influenza infections | Nat Commun. 2013 Jul 3;4:2106; J Thorac Dis. 2013 Aug;5(Suppl 2):S127-31 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | ISME J (2009) 3:944–54. PLoS One (2011) 6:e20647. Acta Paediatr (2012) 101:1121–7. Microbiome (2013) 1-13 und 14-20PLoS One (2013) 8:e83304 |

| Parkinson’s Disease | Mov Disord 2015;30:350–8 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | Immunity. 2016 Apr 19;44(4):875-88. FEBS Lett. 2014 Nov 17;588(22):4244-9 |

Therapeutic approaches and perspectives

From a preventive point of view, a diverse and balanced diet is the most important prerequisite for a healthy and resilient microbiome, i.e. a homeostatic system capable of balancing out normal fluctuations and minor changes in its composition. Once this composition or its interplay with its human host is disturbed, however, therapeutic approaches for the restoration of a healthy intestinal flora need to come into force, such as fecal transplantation, probiotic/ metabolic therapies or targeted delivery of encapsulated microorganisms.

as of 2017